IN A CURIOUS twist, the lavish obituaries that have flooded the media since MF Husain died have triggered a disquieting guilt in me. A sort of selfish sense of loss. Husain understood the value of spectacle like no other: he had spent a huge part of his life engineering it. But now, even as he would have accepted the grand memorials his admirers placed at his door, a part of him would have shifted feet with impatience. There was something Husain wanted keenly in his last years that has remained unattended.

For all his infectious flamboyance — his ambitious projects, his dashing between Dubai and Qatar and London — Husain was a little tired of the obeisance to brand ‘MF Husain’, the surface phenomenon of his tremendous success. “Too much has been said and written about my work,” he once told me. “I want you to tell the story about my life.”

I only knew Husain in the last five years, but he asked me several times to stay a few weeks with him in Dubai and talk and write about the people and thoughts and incidents that had moved him: the inner life of Maqbool that had sustained even as the more public MF Husain blazed a meteoric trail across the world. I wanted to, but never did. I kept putting it off for tasks more urgent and quotidian. Husain was 95. But one always thought he had time on his side. Such was his special gift for youth.

This is not a wreath for a public giant then, but fragments of personal stories he may have wanted to tell. Scattered petals of memory owed to the man.

HUSAIN HAD a fascinatingly liquid quality: a sort of capacity to fit any circumstance, be everywhere and nowhere at the same moment. Perhaps he really did possess a secret elixir: he had cracked the profound paradox that frees the human spirit — the capacity for great love but little attachment.

“It is a mother’s love that creates a sense of home and ties one down. Since I lost my mother when I was one-and-a- half, I have never known such attachment. I also lost my first child Shabir when he was three. I lifted his body out of a gutter. What is loss after that?” Husain had once said ruminatively, over a steaming cup of midnight tea. And so he lived in the midst of a sprawling family and increasing wealth with the inexplicably light feet of a fakir.

But love — many-splendoured, reckless, bound by no rule — was still his inspirational force. Husain had many loves — some of body, some of soul. Of all those, perhaps Maria’s story is the one he would have liked to remember most in greater public detail.

Husain had married impossibly young. Fazila, the daughter of a kindly neighbour who had soothed his orphaned heart, was a lifeboat, a constant co-traveller to the end of her days but a woman with whom he had no intellectual kinship. Then in 1956, Husain met Maria Zourkova, an interpreter detailed to him on an official visit to Prague. Husain was entranced. Conversation — endless talk of life and art — lit their time together. Their relationship — intense, all consuming — lasted several years but was never consummated. Maria was a staunch Catholic: for her, Husain, a Muslim, already married, was a forbidden passion, sheer anathema. During a particularly stormy fight, Maria accused Husain of being a chauvinist who could never give up any part of himself or know how to really love a woman. Stung, the next day — in a sublimely poetic act — on the eve of his prestigious show in Prague, Husain walked into her room, beard gone, completely clean-shaven: a man willing to lose his identity for love. He also dedicated his entire show to her. Maria relented. Marriage seemed a possibility.

Husain hurried back to India, explained things to the hurt but ever constant Fazila and asked for a cosmetic divorce. (He even ensured she married a friend who would not exercise his marital rights, so that he could return and remarry her.) Then in a fever of excitement, Husain went to Europe, borrowed a car from a friend and drove alone across the Alps to Maria. When he reached Prague, he found a letter instead of the woman he loved. Maria was certain they would never be able to surmount their cultural difference: she had chosen to marry her Icelandic suitor instead.

Husain did not meet Maria again for nearly 40 years,but she flowed in his veins as a kind of celebratory sorrow: a sense of the potency of what could have been. Finally, years later, she invited him to Australia so she could return the 80 paintings he had given her. The paintings —worth crores — belonged to India, she said. In that single act, void of all avarice, she reaffirmed the idea of the woman he had idealised for close to half a century.

Towards the end of his days — perhaps a little panicked by all that was left unsaid; perhaps as a subtle amendment for all the years he had floated free in his head, unpossessed by all who loved and lived off him — Husain had started a joyful family ritual. Every Friday, he would gather the many pieces of his family together at a vast ceremonial lunch-table in Dubai and trade memories and insights. Taking the trouble to write his thoughts on bits of paper, he would read from the head of the table: the world already knew the prodigious painter. He had just started to sketch out the man.

One of the most wonderful snatches by which to remember Husain then is perhaps this: even as the big themes of nation, culture, exile and censorship swirled around him, here was a man who could teach the pleasures of caramel popcorn and an unplanned matinee show to nieces and nephews more than half a century younger than him. What greater homage can man pay to life than to love it covetously at 95?

PRECIOUSLY, MY own friendship with Husain — only a tiny pixel in the thousands of mega pixels that made up the screen of his life — began with a fight.

Legends have a way of coming in mixed packages. The legend of MF Husain came streaming whimsicalities like ribbons on an extravagant present. His elusiveness. His unpredictability. His mood swings. Quivering internally at the prospect of all that, I had gone to Dubai in 2007 to coordinate Husain painting a canvas for TEHELKA, jointly with Shah Rukh Khan. Those were difficult years for TEHELKA. We needed the canvas for a fund-raising art auction at Bonhams, London. We needed every genie in the bottle.

Husain walked into her room, clean-shaven: A man willing to lose his identity for love

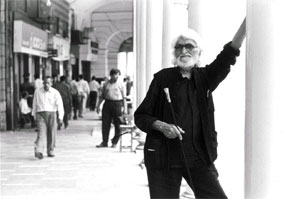

Husain sat like a magnificent self-portrait in a plush five-star hotel lobby: snow-white hair, black galabandh, an oversized paintbrush in hand as a prop. The meeting lasted five minutes. I was an ingénue in the ways of the art world: he read through me like an X-ray machine. Who is the buyer? he asked. What price will the canvas go at? I had no answers (we hadn’t even got the canvas yet, how were we to know who would buy it?) He left in a huff. I had expected to meet a master painter; I had bumped into a marketing fiend instead.

Husain sat like a magnificent self-portrait in a plush five-star hotel lobby: snow-white hair, black galabandh, an oversized paintbrush in hand as a prop. The meeting lasted five minutes. I was an ingénue in the ways of the art world: he read through me like an X-ray machine. Who is the buyer? he asked. What price will the canvas go at? I had no answers (we hadn’t even got the canvas yet, how were we to know who would buy it?) He left in a huff. I had expected to meet a master painter; I had bumped into a marketing fiend instead.

I was frantic. Shah Rukh was due to fly to Dubai the next day. Getting the two together had been like launching a lunar mission. (Shah Rukh, as elusive as Husain, had only replied when I had sent him an exasperated message that said, “Do you exist? Are you for real? Or are you a unicorn?”) And now, here was Husain, playing to the legend, upturning the cart.

Over the next two days, Shah Rukh and I played a surreal game of tag with Husain. Shah Rukh had promised to mollify him but when we arrived at his door we found Husain had flown overnight to Qatar. Eventually, many crazed ECGs later, the canvas did get done — live at Bonhams, in front of an unprecedented audience of 1,500. Husain’s masterstroke.

A year later, relations considerably warmer but not quite friends yet, I went to Dubai to write a profile of Husain (The Master in his Absurd Exile, TEHELKA, 2 February 2008). The Hindu culture police had been up to their vandalising games again. We felt the need to repudiate them and foreground what Husain had really meant for India before a lifetime of work was reduced to a few contentious canvases.

Husain invited me to stay at his home in Dubai. On the first day, we quarrelled fiercely

Generously, Husain invited me to stay at his house — one wing of it, a beautiful apartment done in drapes of red, mischievously called The Red-light Museum (“The name makes people sit up,” Husain had chuckled). It was one of the most memorable weeks of my life. Husain was a great raconteur, and yet a movingly reflective conversationalist. He spoke of India and Hindu iconography for hours with unmistakable love. He would wake up at six, from a simple mattress on the floor, surrounded by giant canvases in various stages of completion, and keep going till after midnight: lunch at his favourite Noodle Bar, afternoons spent painting, a film in the evening (to check out if Deepika Padukone was worthy of a muse), a turn in one of his luxury cars, dinner at Ravi’s dhaba and hours of conversation and tea afterwards.

On the very first day, we quarrelled fiercely. As the sun set over the quay, Husain began to haggle with me over the percentage TEHELKA owed him from the canvas he had made for us. I defended TEHELKA hotly, listing the values it stood for and the hard journalistic work it had done at what cost — questioning his need to eke out more material wealth from his work than he had already got. Husain listened, then lapsed into a long silence. He was sketching a wedding card for Ustad Amjad Ali Khan’s son. Suddenly he said, “Let me make something for you.”

Ten minutes later, he handed me a sublime Durga in fluid motion, mounted on a lion. “You fight like Durga,” he said. “You have her spirit.” I couldn’t have imagined a confrontation buried with more generosity.

Husain did not just have a gift for youth and life: he had a gift for friendship, for boundaries dissolved in sudden good faith. A few months later, when the courts threw out some of the cases against him, I called him for a sound byte. “You already know what I feel,” he said with characteristic disregard for the rulebook, “write anything on my behalf. I give you full power of attorney.”

I wish I had heeded him a little earlier and visited him in time. I could have been a better ventriloquist now. And exercised better power of attorney.

Also Read: The Master In His Absurd Exile